|

| 3.2.2 |

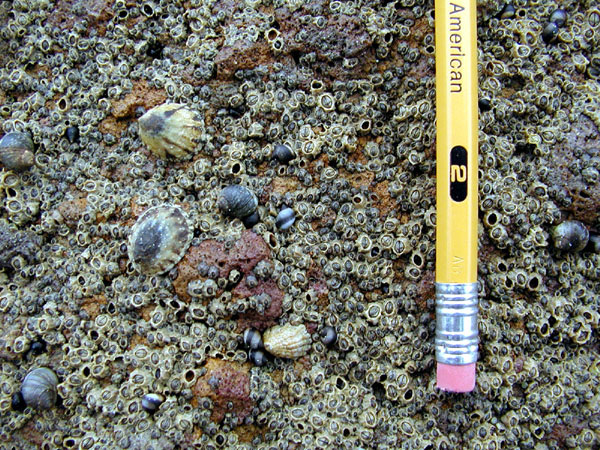

The Splash Zone(sometimes called Zone 1)Splash Zone Now let's begin with the Splash Zone and work our way down. The very best place to see the Splash Zone is at the Santa Barbara Breakwater.  The top of the seawall is 13 feet above sea level and gets splashed with waves at every high tide. Neither Coal Oil Point nor Carpinteria have rocks that are this tall and thus have limited Splash Zones.  Periwinkle Snails Now for the first critter. Like 'King of the Mountain,' the little periwinkle snail prefers to crawl up above the highest water level to the area that gets just the smallest splash from the highest high tide waves. It has the record for the marine animal that can stay out of the ocean the longest. Some remain above the splash of the ocean for two to three months.  Periwinkles, also known as Littorina planaxis, rarely are over three-quarters of an inch. They come in an unbelievable assortment of shell colors and patterns.  From uniform dull gray to shiny shells checkered or striped with white, these snails often cluster together in a crack or crevice.  They secrete a special mucus around the opening to their shell. This hardens, cementing them to the rocky shore. They spend days like this without expending any energy - just 'hanging out' on the rocky surface.  When they are hungry they emerge, first eating the hardened mucus and then they crawl about leaving slime trails, like land snails. They glide along; scraping the plant scum off the rocky surface with a special structure in their mouth called a radula.  This radula is common to many molluscs and is similar to a mini chainsaw - having rows and rows of sharp, hooked teeth for scraping. In fact, they are so efficient that they wear away the rock in some areas, deepening the high intertidal pools. You can imagine that the teeth get pretty dull quickly. This is no problem for a mollusc that continues to produce new rows of radular teeth its entire life - dropping off the old dull ones at the end of the radula. Periwinkles can replace up to seven rows of teeth a day.  These critters are real couch potatoes - many only eat every two to three weeks, spending the bulk of their life cemented to the rocks, with a rare splash of seawater. Hot sun, rain and wind do not bother them. They have a 'door,' called an operculum, which keeps them protected. It is on their tail and closes their body inside their shell while they are resting - keeping in moisture on the driest days.  Once a year they expend extra energy in reproduction. These snails are separate sexed - the male needing to find a female for mating. In this species, the males appear unable to distinguish the opposite sex until actually trying to mate. In spring and summer males become very active - trying all neighbors for a possible mate and even fighting. Sometimes two males will be fighting over a third snail only to discover that the third snail is also a male. Eventually they are successful and, after mating, the female lays her fertilized eggs in a mucus bundle in high pools. These hatch as planktonic larvae and are taken away by the extreme high high tide waves.  Rarely do periwinkles encounter predators because they are so high, but if they fall down, off their high and dry perch, they may be eaten by sea stars, crabs, or sea anemones. As you move closer to the five foot level you encounter fingernail limpets and buckshot barnacles in the Splash Zone along with a few periwinkle snails.  Fingernail Limpets  Now let's move down a bit, just over the five-foot level. Only the size of a fingernail, the fingernail limpet (also called the rough or ribbed limpet, Collisella scabra and Collisella digitalis) is also a grazer, just like the periwinkle snail. Limpets are closely related to snails, but lack the coiled shell and operculum. There are several species of fingernail limpets, some with rough edges, and some with smooth edges.  Lacking an operculum, (like the periwinkles use to avoid dessication), these fingernail limpets have a neat trick to avoid desiccation. They make the edge of their cap-shaped shell the exact configuration of the rock where they live and just pull down for a tight fit, keeping water inside. This special spot on the rock is known as their home scar.  When covered with a high high tide, these critters come out cruising. Having only about six hours each day under the water, they travel along the rocky surface near their home scar, scraping the algae off the rocks with their radula, just like the periwinkles. After eating, these limpets usually return to their home scar before the tide recedes, so they can pull down and seal in moisture. It is unknown exactly how they find their home scar, but their tentacles appear to be more important than their eyes.   Although they are separate sexed (like periwinkles) they have no interest in mating. They have a unique reproductive mechanism, called broadcast spawning, to ensure fertilization. This is commonly found in many marine species and is accomplished by simply releasing eggs and sperm into the ocean. The swirling ocean water is where fertilization occurs. In order to assure fertilization, broadcast spawners release thousands to millions of eggs and sperm with each spawning to ensure just one offspring. Limpets have a planktonic larval form, like periwinkle snails, that develops from the fertilized egg.  These limpets share the lower reaches of the Splash Zone with millions of tiny barnacles. Buckshot Barnacles No bigger than buckshot, the buckshot barnacle, Chthamalus spp., can live the highest of all the barnacles along our shoreline, often covering the rocks with over 8,000 per square foot.  Each tiny barnacle is enclosed in grayish-colored shells that can completely close. Once they begin life on the rock, they cannot relocate as these shells are attached permanently to their substrate.  When dead, the outside shell remains as an empty volcano until it degrades but the body and closing shells fall out - leaving empty volcano shells for a time. Without the living barnacle, the volcano shell eventually weakens and falls off. You might wonder how so many can be found together in such a severe environment. One reason is that few predators venture up here to eat them. They can also close their shells to avoid desiccation.  They have an incredible reproductive style. They are what we call hermaphroditic in biology … that is they are both male and female in the same body. Each animal makes both eggs and sperm, but usually cannot get its sperm to its own eggs. Barnacles have an inflatable penis that is used in mating with a neighbor. This penis can inflate and extend up to 2 inches from the tiny barnacle.  For many of these buckshot barnacles this is 20 times the size of their full body! They mate during all seasons, except winter, and each may produce up to 16 broods a year. After mating, the barnacles' fertilized eggs (usually several hundred to several thousand in each brood) develop to a planktonic larval form that is shed into the water. Most of these never survive as they get eaten by filter feeders in their planktonic stage, or never find a place to settle and become an adult barnacle.  Now what about the 'lone' buckshot … without a neighbor to mate with? It seems that, in nature, if a buckshot barnacle is greater than two inches from any other buckshot then it can fertilize its own eggs (in-breeding).  As you move down, closer to the five-foot tide level, you begin to encounter a larger barnacle, called the balanus barnacle, which cannot tolerate the dryness of the Splash Zone. Now we move to the High Tide Zone. |

(Revised 26 June 2003) |