|

| 3.2.3 |

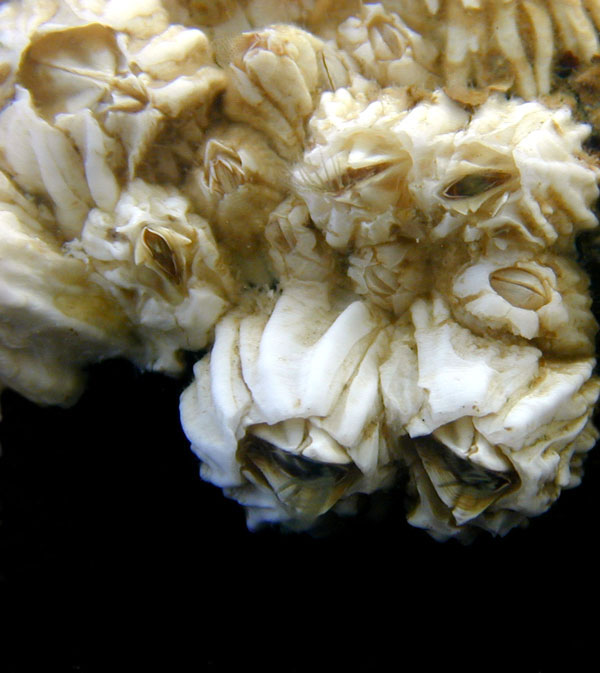

The High Tide Zone(sometimes called Zone 2)High Tide Zone Balanus Barnacles Several species of balanus barnacles, Balanus spp., begin to crowd out and take over space covered by the higher living buckshot barnacles - starting about five feet above sea level in Santa Barbara.  These larger balanus barnacles are much bigger than the tiny buckshots (within a few months of their lives) so are rarely mistaken for the smaller buckshots that remain about 1/8 of an inch in diameter. Like most barnacles, once settled, the balanus cannot relocate. Reproduction is similar to the buckshots (hermaphroditic, mating, planktonic larvae) but they usually only produce 2-6 broods per year and generally during winter.  All barnacles are filter feeders - extending feathery legs into the water at high tide to comb plankton from the water. These 'furry' legs then kick the plankton down into the volcano-shaped shell to the mouth area of the barnacle.  Comb-like structures near the mouth remove the plankton from the legs before they stick out again for more. Barnacles may inadvertently feed on their own babies when they are still planktonic larvae. At the five-foot level you encounter another type of barnacle, the gooseneck barnacle (also called the leaf barnacle). Gooseneck Barnacles  These gooseneck barnacles, Pollicipes polymerus, have the characteristics of the more common volcano-type barnacles (like the buckshot and balanus), in that they are also filter feeders, capable of living rather high in the intertidal, being hermaphroditic, cross fertilizers, and having numerous planktonic larvae. They differ in that their bodies are on top of a permanently attached stalk covered with a thick skin. This stalk is a wonderful seafood (no guts inside) and tastes much like clam when steamed.  They tend to reproduce in summer with 3-7 broods per year. A unique thing about the planktonic larva of this species is that when it settles out of the plankton it generally crawls around, hunting for adults of its species before adhering to a solid substrate. This explains why single goosenecks are rarely seen--even when there is empty space on the rock there are always hundreds of goosenecks crowded together in rounded hummocks.  They can live 20 years, or more. As they grow they make new calcareous plates protecting their bodies. When first secreted, these plates are shiny and pearlescent. After repeated high tides and battering waves (with sand and rocks), the pearly shells become pitted and dull.

It is interesting to look through these masses of gooseneck barnacles in our tidepools and see newly secreted shells. This means that the barnacle is happy, healthy and growing.  Mixed in with the gooseneck and the balanus barnacles is the most common member of the High Tide Zone - the mussel.  Mussels Starting at about five feet above sea level, it is the California mussel, Mytilus californianus, that dominates Santa Barbara rocky shorelines exposed to waves. The mussel does not do well above this height, unless in a protected crack, as it is too dry.  The mussel is a space dominator - attaching itself with an array of exceptionally strong byssal threads. Each of these is laid down individually by the animal's soft and flexible foot, which protrudes from between the two shells at high tide until it touches a solid surface. A special liquid is secreted inside that runs down a groove in this foot and out the end. This liquid is like super glue and hardens as a small pad at the bottom attached to the surface. As the mussel withdraws its foot, the liquid continues to harden, producing a strong thread attached to the inside of the animal's body. Numerous byssal threads are laid down by each mussel to keep it attached.  When they are young they can loosen their threads and move about a bit, but when they are older most of them stay put. They do not hesitate to grow on top of each other and other species - resulting in interesting mussel clumps that are themselves a habitat harboring over 100 species of marine organisms.  Mussels open their shells just a crack at high tide to feed, which allows them to circulate 2-3 quarts of seawater through their shells each hour - mucus on their gills traps plankton for their food. When there is a lot of plankton mussels can grow up to three inches each year and will overgrow most other species. But … although they dominate the area between 2.5-5 feet above sea level, in Santa Barbara, they rarely get a chance to live lower in the intertidal because their main predator, the sea star, consumes them. Studies done by scientists who remove the sea stars from rocky intertidal areas show that mussels will prevail all the way to 20 feet below sea level as giant clumps if left unchecked by their natural predator. Other factors also affect them, like big waves tearing off clumps, that get too large, or parasites, but it is the sea star that has the most influence.  Large rocks in the intertidal that span two and a half feet above sea level show a distinct line of zonation where the mussel-dominated High Tide Zone and the Mid Tide Zone meet. At two and a half feet above sea level (about as high as sea stars will go to feed), Santa Barbara's rocky shores show a marked change as mussels disappear and the aggregating anemone becomes the dominant species. We now enter the Mid Tide Zone--dry only a quarter of an average day when it is low low tide.  |

(Revised 26 June 2003) |